A HISTORICAL TRAGEDY: THE INHUMANE REALITIES OF THE TUSKEGEE SYPHILIS STUDY

BY LUGHANO MWANGWEGHO

The Tuskegee Syphilis Study, officially called the Tuskegee Study of Untreated Syphilis in the Negro Male, is one of the darkest and most disturbing episodes in the history of medical research in the United States. Held by the U.S. Public Health Service (USPHS) from 1932 to 1972, this long-term study claimed to investigate how untreated syphilis progressed in African American men. However, it ultimately highlighted severe ethical breaches, racial exploitation, and widespread human suffering.

The study launched during the harsh realities of the Great Depression in Macon County, Alabama, where poverty was rampant, and access to healthcare was painfully limited. Researchers drew in 600 African American men, of whom 399 had latent syphilis, while 201 served as a control group without the disease. The men were misled to believe they were receiving treatment for “bad blood,” a term in the local vernacular that referred to various ailments. In truth, the study’s objective was to observe the course of untreated syphilis, and instead of proper medical care, participants were given placebos, trivial remedies, and procedures that masqueraded as treatment.

What was intended as a brief study tragically morphed into a lengthy torment that lasted for 40 years. Initially, there was no effective cure for syphilis; however, by the mid-1940s, penicillin emerged as a safe and reliable treatment. Despite this medical advancement, researchers chose to withhold the cure from the infected men, actively blocking their access to the treatment that could have saved their lives. This denial was not a matter of ignorance but a calculated decision; the leaders of the study feared that treating the men would end their ability to observe the disease in its natural progression.

The fallout from this unethical study was dire. Many participants faced significant health issues, including cardiovascular and neurological problems, blindness, mental illness, and death due to untreated syphilis. It is estimated that over 100 men died as a direct result of syphilis or its related complications. Additionally, the disease extended to at least 40 wives and led to 19 cases of congenital syphilis in their children.

The veil of secrecy and ethical malpractice surrounding the study was lifted in 1972 when a whistleblower brought the information to light, leading to public outrage and scrutiny. An advisory panel quickly deemed the research unethical, and the study was swiftly terminated. This led to a class-action lawsuit filed by the participants and their families, culminating in a $10 million out-of-court settlement and medical benefits for survivors and their dependents. In a historic moment in 1997, President Bill Clinton issued a formal apology on behalf of the U.S. government, acknowledging the deep moral injustices inflicted by this infamous study.

THE TRAGIC STORY OF OTTO WARMBIER

By Lughano Mwangwegho

Otto Frederick Warmbier was a young American college student. His trip to North Korea ended badly and became known around the world. His story showed how dangerous it can be for Western visitors in strict and authoritarian countries.

Otto was born on December 12, 1994, in Cincinnati, Ohio. He studied at the University of Virginia and was curious about other countries. In late December 2015, he joined a guided five-day tour to North Korea which is known for strict rules for visitors and very harsh laws.

The tour was organized by a company in China and was advertised as an adventure. On January 2, 2016, as Otto was leaving Pyongyang to travel to Hong Kong, he was arrested at the airport. North Korean officials said he tried to take a political poster from a staff-only area of his hotel. In North Korea, this was considered a serious crime, so he was detained immediately.

In March 2016, Otto appeared in North Korea’s Supreme Court. The trial lasted about one hour. He was found guilty and sentenced to 15 years of hard labor. The court showed a video in which Otto confessed. However, many people around the world believed the confession was forced, because North Korea does not have fair and open courts.

Shortly after he was sentenced, Otto Warmbier’s situation became very serious. North Korean officials later said he had a severe brain injury and was in a coma. They blamed it on food poisoning and a sleeping pill, but his family and Western doctors doubted this. For 17 months, he stayed in North Korea in an unresponsive state, and very little information was given to his family or the world.

In June 2017, North Korea agreed to release him for “humanitarian reasons.” He was flown back to the United States and taken to the University of Cincinnati Medical Center. Doctors said he was in a state called “unresponsive wakefulness,” with severe brain damage and no signs of awareness.

Otto never woke up, and six days later, on June 19, 2017, his parents decided to remove life support. His death caused international outrage. It drew attention to human rights issues in North Korea and the dangers for foreigners under its strict laws. The U.S. government condemned his treatment, and Americans were later banned from traveling to North Korea. Otto’s parents sued the North Korean government, and in 2018 a U.S. court awarded them damages, holding the regime responsible for his suffering.

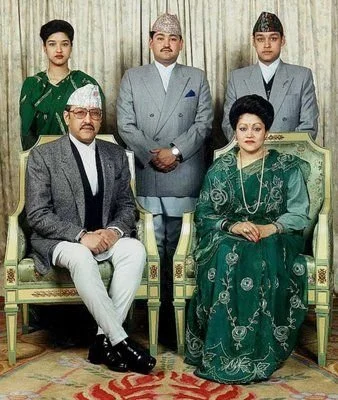

THE ROYAL MASSACRE OF NEPAL: A TRAGEDY THAT SHOOK A NATION

On 1 June 2001, Nepal experienced one of the most shocking and tragic events in its modern history—the Royal Massacre at the Narayanhiti Royal Palace in Kathmandu. This event not only brought the brutal deaths of key members of the Shah dynasty but also triggered political upheaval, widespread grief, and long-lasting controversy that would ultimately contribute to the end of Nepal’s centuries-old monarchy.

The massacre occurred during a private family gathering, a routine weekly event that the royal household held every Friday. According to the official version of events, Crown Prince Dipendra Bir Bikram Shah—the heir to the throne—allegedly opened fire on his relatives after a heated argument, reportedly related to his desire to marry Devyani Rana, a match opposed by his parents. Dipendra is said to have returned to the palace dressed in combat fatigues and armed with multiple weapons, and then shot several members of his family in a violent outbreak that lasted only minutes.

The casualties were devastating. Among the ten members of the royal family killed were King Birendra, Queen Aishwarya, Prince Nirajan, Princess Shruti, and other close relatives. Crown Prince Dipendra himself was found critically wounded, having turned the weapon on himself; he remained in a coma for three days before dying on 4 June 2001. In an unusual constitutional procedure, Dipendra was declared king while comatose, but his reign lasted only until his death. His uncle, Gyanendra Shah, then ascended the throne.

The massacre plunged Nepal into profound national trauma. King Birendra was deeply respected by many Nepalis and was seen as a stabilizing figure who had played a key role in transitioning Nepal toward a constitutional monarchy in the 1990s. His sudden and violent death, along with that of nearly the entire royal family, left the population in shock, confusion, and disbelief. Public mourning quickly turned to anger and suspicion as many questioned how such an atrocity could have occurred and whether the official explanations were complete.

In the immediate aftermath, Gyanendra’s ascension to the throne was met with controversy. Although legal under succession laws, his rise was viewed with suspicion by segments of the population, partly because he was absent from the palace at the time of the shootings and partly because of the opaque nature of the subsequent investigation. The massacre also weakened the legitimacy of the monarchy at a time when Nepal was already grappling with a growing Maoist insurgency, further destabilizing the political landscape.

The long-term consequences of the massacre were significant. The mistrust and disillusionment it engendered contributed to a broader erosion of support for the monarchy. Over the next several years, Nepal experienced escalating political turmoil, including King Gyanendra’s attempt to assume absolute power in 2005, which provoked mass protests and ultimately reinforced republican sentiment. In 2008, just seven years after the massacre, the monarchy was abolished and Nepal became a federal democratic republic, ending over 240 years of Shah dynasty rule.

Despite official accounts, many Nepalis remain skeptical about the true motives and circumstances behind the massacre. The rapid cremation of the royal bodies, lack of independent forensic evidence, and unanswered questions about key details have fueled alternative theories ranging from palace conspiracies to foreign involvement. These lingering doubts reflect the deep emotional and political impact the massacre had on Nepal’s collective psyche.

USA - Small plane crashes into building in Philadelphia

A small plane crashed into buildings

Black Hawk helicopter crashes into American Airlines plane killing all on board

Military helicopter collides with American Airlines plane, killing all on board

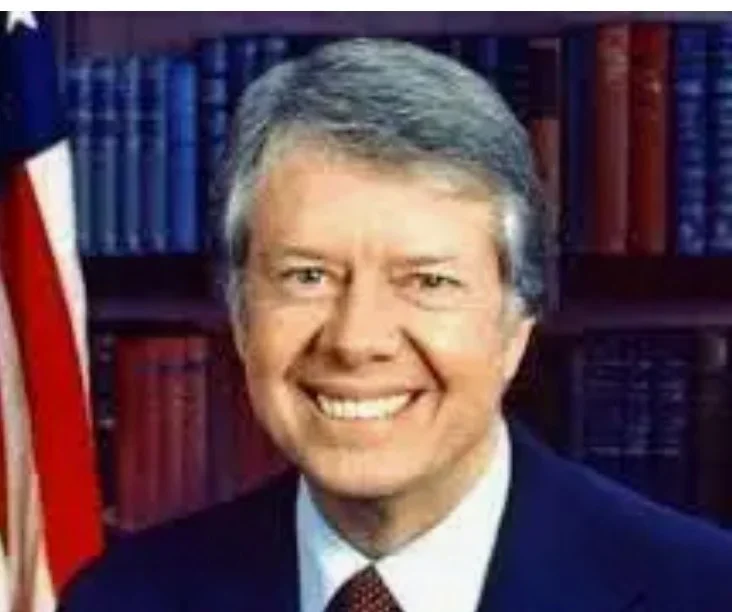

Jimmy Carter, 39th President of the USA, dies at the age of 100

President Jimmy Carter dies