THE RISE AND FALL OF JIANG QING: MAO ZEDONG’S CONTROVERSIAL WIFE

BY LUGHANO MWANGWEGHO

Mao Zedong (1893–1976) was the founding leader of the People’s Republic of China, revered by some as a revolutionary who unified a fragmented nation and helped it modernize. Yet, his drive to reshape China through sweeping social and economic campaigns had tragic consequences for ordinary people. In the late 1950s, Mao launched the Great Leap Forward, a radical attempt to industrialize and collectivize agriculture. Instead of prosperity, this policy brought widespread disruption to farming and food production. Local officials were pressured to report inflated crop yields, prompting the state to take grain that villagers desperately needed. The result was one of the deadliest famines in history, with most scholars agreeing that millions — often cited around 30 million — died from starvation and related causes, and many families were torn apart as they struggled to survive.

When Mao Zedong died in September 1976, the tight circle of leaders around him quickly lost their most powerful protector. Among them was Jiang Qing, Mao’s third wife, who had risen from being a Shanghai-stage actress to one of the most influential — and feared — figures in China’s government during the Cultural Revolution. For a decade she was more than just “Madame Mao”: she was a leader of a faction known as the Gang of Four that helped drive the Cultural Revolution’s radical campaigns. Under her influence, traditional culture was suppressed, schools and universities were closed, and young militants known as Red Guards were encouraged to root out “bourgeois” and “counter-revolutionary” elements. People’s lives were turned upside down as professors, artists, party officials and many ordinary citizens were publicly humiliated, driven from their jobs, imprisoned, or worse — in hundreds of thousands of cases — persecuted or killed during this period of social upheaval. Jiang’s name became associated with the Cultural Revolution’s excesses and the suffering of millions caught in the chaos of ideological purges and violent factional struggles.

After Mao’s death, her privileged position disappeared almost overnight. In October 1976, just a month later, she and her closest allies were arrested by Mao’s successors, who sought to end the Cultural Revolution and stabilize the country. Branded responsible for the decade of turmoil, Jiang was expelled from the Communist Party and, in 1980–1981, put on trial in a highly publicized case that was broadcast across China. She was convicted of “counter-revolutionary crimes” for her role in inciting unrest and political persecution, and initially sentenced to death with a two-year reprieve — a common practice that allowed authorities to review conduct before execution. In 1983 her sentence was commuted to life imprisonment. She spent the rest of her life in custody, and in May 1991, while on medical parole, she took her own life at the age of 77. Jiang Qing’s dramatic rise and fall — from powerful political figure to imprisoned outcast — mirrored the broader upheavals of modern China and left a deep imprint on the nation’s collective memory of the Cultural Revolution era.

HIROO ONODA: A MAN CAUGHT BETWEEN DUTY AND REALITY

LUGHANO MWANGWEGHO

Hiroo Onoda’s life reads like the story of a soldier, a ghost, and a man trapped in time. Born on March 19, 1922 in Wakayama, Japan, Onoda grew up in a society steeped in tradition, duty, and respect for authority. These values shaped him deeply. His family had a military background, and when he was conscripted into the Imperial Japanese Army in 1942, he accepted service not as an abstract idea, but as a personal mission. For Onoda, duty was not something to bend — it was something to live and die by.

In December 1944, at the age of 22, Onoda was sent to Lubang Island in the Philippines with a clearly defined guerrilla mission: to harass the advancing Allies, destroy infrastructure, and never surrender, no matter what happened. These orders included an explicit directive that he must survive — even if it meant living off coconuts or other jungle food until reinforcements arrived. This promise from his superior officer, which someone would return for him, stayed with Onoda for years — a personal contract he felt bound to honor.

When World War II ended in August 1945, Japan’s surrender was broadcast, announced, and printed on leaflets. But for Onoda — deep in the rainforest, cut off from communication, and trained to distrust enemy messages — these notices felt like traps designed to fool him. He, like many soldiers trained in unwavering obedience, saw every attempt to convince him of peace as deceit. Even a message left by locals saying “the war ended” was dismissed as propaganda. His devotion was not blindness but the product of belief and conditioning — he was doing exactly what he was taught to do.

Life in the jungle was harsh. Onoda and his comrades survived on coconuts, bananas, stolen rice, cows they killed for meat, and whatever provisions they could scavenge. Rain, insects, solitude, and the unknown pressed in constantly. Over the years, exhaustion, hunger, and the loss of his friends — one surrendering in 1950, two others dying in combat — shaped him, graying his world into endurance alone. By 1972, Onoda was the last holdout.

But Onoda was still human. When a young adventurer named Norio Suzuki finally found him in 1974, something unexpected happened. Suzuki didn’t just announce that the war was over — he spoke to Onoda as a fellow human being, not as an enemy or a target. Their conversation forged a connection that broke through decades of isolation. Yet even then, Onoda did not surrender — not until an old promise was honored. He insisted only a direct order from his commanding officer could end his mission.

When his former commander, Major Yoshimi Taniguchi, arrived and gave that order, Onoda wept as he finally laid down his rifle and sword. For the first time in nearly 30 years, he faced a world that had moved on without him. The jungle that had been his protector became a memory; the war he had lived in faded into peace.

Onoda’s homecoming was surreal. Japan had transformed into a modern, thriving society — a place of technology, skyscrapers, and peace. For a man who had lived almost three decades in the jungle, the change was staggering. He struggled to reconcile what he had believed with what the world had become. At times he said that his time in the jungle had shaped him deeply — that without those years, he wouldn’t be the man he was.

HIROSHIMA AND NAGASAKI: LIFE AFTER THE BOMBS

BY LUGHANO MWANGWEGHO

In Hiroshima, the morning of August 6, 1945, brought a blinding flash. People who had been walking, shopping, or going to work were suddenly thrown into chaos. Streets were filled with smoke and rubble, and cries for help echoed everywhere. Some survivors dragged themselves from the ruins, their clothes burned, their skin blistered, searching desperately for family members who were never found.

Three days later, Nagasaki faced the same horror. Fires raged through the city, and hospitals overflowed with injured people. Survivors walked through streets where buildings had vanished, carrying friends and strangers to safety, often with nowhere to take them. Water was scarce, and many drank from contaminated sources, worsening sickness caused by radiation.

THE LASTING EFFECTS OF THE HIROSHIMA AND NAGASAKI BOMBINGS

The atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki in August 1945 were catastrophic events that ended World War II but left long-lasting consequences that are still felt today. While the immediate destruction killed tens of thousands of people and flattened entire cities, the long-term effects of the bombings have continued to impact survivors, their descendants, and the world at large. These effects can be seen in health, society, the environment, and global politics.

One of the most significant and ongoing effects is on human health. Survivors of the bombings, known as hibakusha, were exposed to extremely high levels of radiation, which caused severe burns, radiation sickness, and long-term illnesses such as cancer and leukemia. Even decades later, many survivors suffer from chronic health problems, including cataracts, weakened immune systems, and cardiovascular diseases. Studies also show that some children born to survivors carried the effects of radiation exposure, although these genetic effects have diminished over generations.

The psychological and social effects of the bombings are equally profound. Survivors were forced to endure unimaginable grief, losing family members, friends, and their homes. Many experienced post-traumatic stress, depression, and survivor’s guilt. In addition, some hibakusha faced social stigma, as communities feared that radiation could be inherited by their children. These emotional and social challenges have shaped Japanese society and influenced how survivors live and interact with the world even today.

Environmental and urban effects also continue to be felt. Both Hiroshima and Nagasaki had to be completely rebuilt after the bombings, a process that took years and changed the cities’ landscapes forever. Today, these cities stand as symbols of peace, with memorials, museums, and parks reminding people of the human cost of nuclear weapons. While radiation levels decreased quickly, the initial contamination affected land use, agriculture, and public health in the short term, leaving a lasting mark on the environment.

Globally, the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki had far-reaching political effects. They highlighted the destructive power of nuclear weapons, prompting international debates on arms control and non-proliferation. The events spurred movements for nuclear disarmament and led to the creation of treaties aimed at preventing the future use of such weapons. Hiroshima and Nagasaki have become centers for peace education, reminding the world of the dangers of nuclear warfare and the importance of diplomacy over conflict.

THE DOWNFALL OF NICOLAE CEAUȘESCU

BY LUGHANO MWANGWEGHO

Nicolae Ceaușescu was the communist leader of Romania from 1965 to 1989, ruling first as head of the Party and later as president. Initially noted for asserting independence from Soviet influence, his government became increasingly repressive and authoritarian, tightly controlling free speech and dissent through the secret police. Ceaușescu used intrusive policies — such as banning most abortions and contraception to boost birth rates — which led to unsafe pregnancies and a rise in abandoned children. In the 1980s he imposed harsh austerity measures to repay foreign debt, causing severe shortages of food, fuel, and medicine and lowering living standards for ordinary Romanians. Historic districts and entire villages were demolished under his systematization policies, displacing thousands. Widespread discontent exploded into revolt in December 1989, and after a brief trial Ceaușescu and his wife were executed on December 25, 1989, as the regime collapsed.

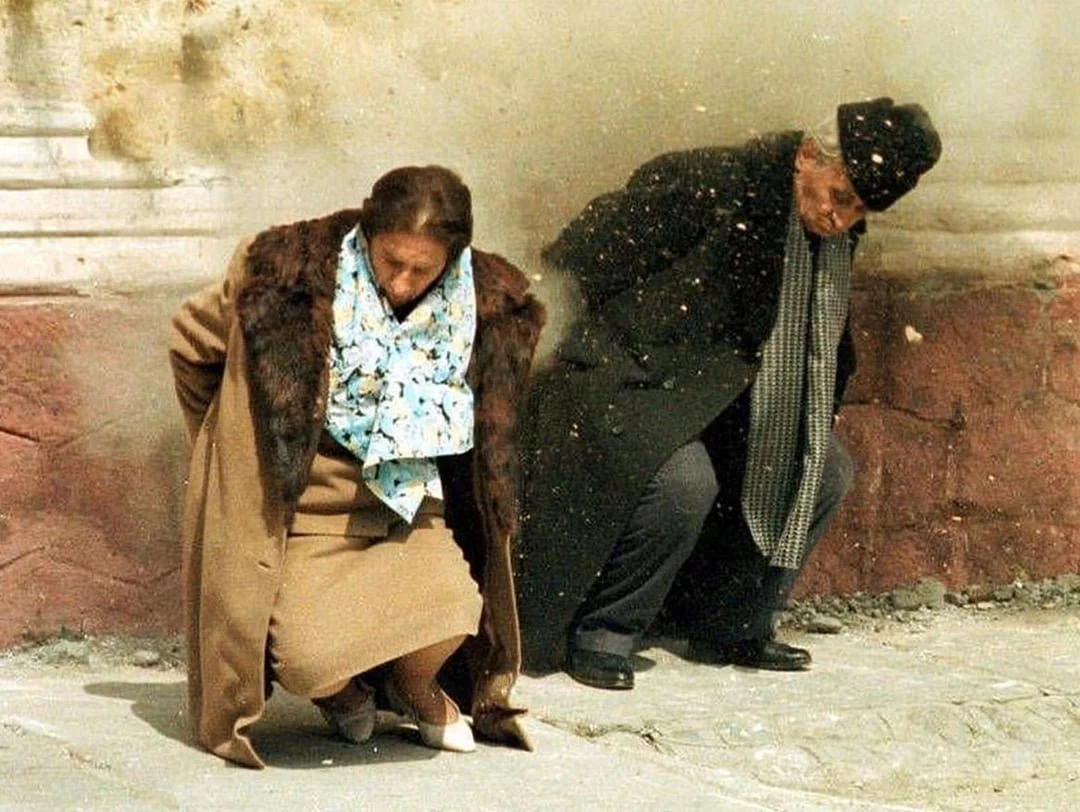

In the final days of December 1989, Nicolae Ceaușescu—Romania’s long-time communist leader—was facing the most intense crisis of his rule. Nationwide protests had erupted in response to his harsh policies, especially after security forces killed demonstrators in the city of Timișoara, sparking wider unrest throughout the country. As demonstrations spread to the capital Bucharest, crowds demanded change and the army began to refuse orders to fire on civilians. With public support collapsing and the streets filled with protesters, Ceaușescu made one of his last public speeches on December 21 that was meant to show strength but instead only showed how isolated and out of touch he had become, as even the crowd began cheering against him and turning hostile.

Realizing he had lost control, Ceaușescu and his wife Elena fled Bucharest by helicopter on December 22, trying to escape the growing revolt. Their flight took them first to Ceaușescu’s residence and then toward Târgovişte, but the army ordered their helicopter to land, and they were captured by forces loyal to the new provisional authorities.

For the next few days they were held under guard, while Romania was engulfed by uncertainty and violent clashes between different armed groups and civilians. On December 25, 1989, after a short, improvised military trial in Târgovişte, Nicolae and Elena were found guilty of crimes including genocide and abuse of power. They were quickly sentenced to death and executed by firing squad that same afternoon, bringing an abrupt and dramatic end to decades of dictatorship.

Their downfall came not with a calm resignation but with a sudden collapse of authority, a failed speech broadcast to the nation, a chaotic flight, and a rapid trial—events witnessed by a country exhausted by repression and yearning for change.

Fears it might be too late to deflect asteroid headed towards earth

Asteroid headed towards earth

Mexico and Canada announce one-month pause in threatened Trump tariffs

Canada and Mexico tariffs on hold

Deepseek, the Chinese AI app that landed at the top

DeepSeek - The new AI app making waves

Trump to cut aid to many countries in bid to put national interest first

USA to freeze foreign aid

Tiktok starts restoring services for US members after shutting down

Tiktok restored in USA

India’s Festival of Maha Kumbh Mela underway for the first time in 144 years

India's Kumbh Mela festival underway

USA - Delayed launch for Jeff Bezos rocket, Blue Origins

Blue origins rocket launch delayed